People v. Scott Evans Dekraai, 5 Cal. App. 5th 1110 (2016), When Prosecutors Have a Conflict of Interest Due to Their Loyalty to Law Enforcement

This is an extraordinary opinion in an extraordinary case. Although the events of this case arise in Orange County, California, it’s still highly relevant to our practice on this side of the country because of the willingness of prosecutors here to use snitches and informants with (as far as I can tell) no oversight. There’s really nothing to keep this kind of scandal from happening in our neck of the woods. But more broadly, this offers an important view into conflicts of interest between state prosecutors and their law enforcement entities.

Dekraai was charged with a horrific capital crime in California. He was placed in the Orange County jail. Deputy Sheriffs moved a guy named Fernando Perez, a confidential informant, near him. They became “friends” and Dekraai allegedly made incriminating statements to him. Perez wrote down the statements and gave them to his handler, a cop. That information went up the chain, and an assistant district attorney, Senior Deputy DA, an investigator and cop then spoke to Perez. They placed a recording device in Dekraai’s cell and he made additional statements to Perez. Around this time (it’s not clear from the opinion exactly when), he was appointed a public defender.

Perez and another inmate were part of “Operation Black Flag”– they were informants used to combat criminal gang activity in Orange County, in conjunction with the Santa Ana Police Department, the AUSA, and a state deputy DA. His work as an informant was well known to law enforcement.

In light of the government’s conduct of obtaining these recordings, Dekraai’s lawyers filed a number of motions: 1) to dismiss the death penalty based on outrageous governmental conduct, 2) to recuse the Orange County DA’s office pursuant to a state statute and due process clause, 3) to exclude his statements pursuant to Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964) (prosecution may not use evidence obtained in violation of Sixth Amendment right to counsel). The state court held an evidentiary hearing on the motions. The court heard testimony from 36 witnesses.

Among other topics, Perez testified he became a “CI” because it was “the right thing to do” but he hoped his cooperation would be taken into account. He said no one promised him anything. He claimed he did not ingratiate himself to anyone to get them to talk– but he acknowledged he had an incentive to have them cooperate because he was facing two life sentences. Perez provided information on numerous inmates. The state prosecutors did not disclose to Dekraai’s lawyers that Perez had worked for the State in these other cases.

This opinion is extremely heavy on facts, but it is enough to know that, after this first hearing, the trial court denied defense counsel’s motion to recuse the DA’s office. The court found that the DA’s office committed Brady violations (or “errors”) and that the DA’s justifications were not persuasive (i.e. misunderstanding the law, heavy caseloads, uncooperativeness of federal authorities, and failure to anticipate defense strategy). But the court found that the evidence demonstrated that “it [was] more likely than not” law enforcement did not intentionally house Dekraai and Perez in adjoining cells and that “independent events” brought them together. The Court further found insufficient evidence that the DA’s office had a conflict of interest.

FAST FORWARD:

Defense counsel filed a motion for reconsideration based on newly discovered evidence that trial counsel uncovered as the result of a subpoena in another criminal case. The new evidence consisted of so-called “TRED records,” the Sheriff’s Department’s “dated computer entries that include the purported reasons for both jail housing movements and classification decisions.” Lo and behold, there were actual records detailing just how it came to be that Perez, their snitch, was placed in a cell next to Dekraai, facing the death penalty for his crimes.

The court then held a second evidentiary hearing where it was revealed:

- There were thousands of TRED entries for the Orange County Jail that detail why inmates are moved.

- It appears that the officers were discouraged by their superiors from even acknowledging the existence of TRED records.

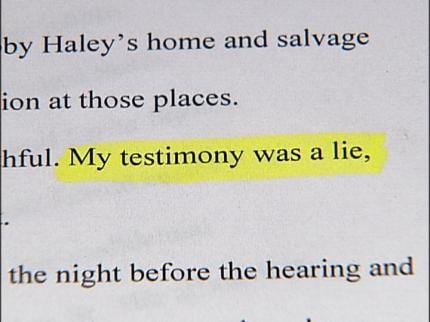

- One of the officers who testified in the first hearing, and who was asked about his testimony in this second hearing, essentially fell apart on the stand and testified that he was told not to discuss TRED entries.

Once the court heard all this, it granted the motion to recuse. The court analyzed the issue under a California state statute that specifically addresses motions to recuse a prosecutor. The court found that the DA’s office had a conflict of interest and that it was “more likely than not” that the DA would treat the defendant unfairly during some portion of the criminal proceedings” (Wow!). Here is some language from the case:

Additionally, we conclude there is other uncontradicted evidence from OCDA employees that supports the court’s conclusion the OCDA’s conflict of interest was so grave it was unlikely Dekraai will receive a fair penalty hearing. Wagner admitted Tanizaki, his direct supervisor, and Rackauckas were aware of Dekraai’s motions and some of the allegations. Wagner also admitted he made public comments the motion included “scurrilous allegations” and “untruths” before he had read the entire motion, which demonstrates he had prejudged its merits . . . How could the trial court expect the OCDA to properly supervise OCSD and fairly prosecute the penalty phase when one of the DA’s prosecuting Dekraai failed to acknowledge any wrongdoing on the prosecution team’s part in the Dekraai case?

Id. 554.

And, using even more powerful language, the court found:

No, the recusable conflict of interest, a divided loyalty, is based on the OCDA’s intentional or negligent participation in a covert CI program to obtain statements from represented defendants in violation of their constitutional rights. The conflict here is “real,” it is “grave,” and goes well beyond simply “distasteful or improper” prosecutorial actions. The trial court’s recusal of the entire OCDA’s office was a necessary step to ensure Dekraai’s personal right to a fair penalty trial.

Id. at 555.

Based on the DA’s office’s “loyalty” to its Sheriff’s Office, at the expense of the defendant’s rights to due process, this court recused the entire office from the prosecution of this case. A very fair and reasoned outcome, and an important lesson for those charged with a duty to seek justice, and not just convict defendants. But it also highlights a more concerning issue (in my opinion) and that is oversight of law enforcement use of informants, especially in state cases. As far as I can tell, there are no guidelines or protocols for their use, and I’ve had two cases now, on appeal, where law enforcement simply did not disclose the use of their informants in other cases (and which would clearly be relevant to bias or interest in the case before the court). Lucky for this defendant, his attorneys were tenacious in their efforts to uncover this abuse.